The Day We Learned Password Resets Don’t Work Anymore

Last week, a friend of mine was hacked, and not in the usual, inconvenient, password‑reset kind of way. This was the kind of compromise that makes your stomach drop. Their email was taken over, and from there the attackers moved with terrifying speed: bank accounts, pensions, savings, everything that could be reset or redirected was suddenly in play.

But the truly frightening part wasn’t the initial breach. It was what happened after they regained control.

They changed the password. They kicked out active sessions. They did everything we’ve all been trained to do for decades. And yet… the attackers were still in. They kept slipping back in as if the password reset didn’t matter at all.

It wasn’t until we dug five layers deep into an obscure security menu that we finally found the problem: a passkey. A credential quietly added by the attackers, completely unaffected by password changes, and invisible to anyone who doesn’t know exactly where to look.

That was the moment I realised something uncomfortable: passkeys, which the industry advertises as safer and simpler, have also created a new kind of risk that almost no one is talking about.

Passkeys: Brilliant Cryptography, Terrible Reality

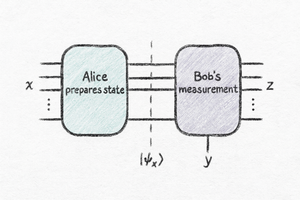

Passkeys are technically superior. They fix entire classes of attacks that have plagued the internet for decades. No more phishing the password. No more credential stuffing. No more brute force. They anchor authentication in something far stronger: asymmetric cryptography.

But while they solve one set of problems, they quietly create a new one—one that most people, and worryingly many platforms, are utterly unprepared for.

Because what passkeys also introduce is a new type of vulnerability: password‑independent persistence. A hacker who manages to register a passkey on your account isn’t just another unwanted guest. They’ve cut themselves a spare key, one your password can’t revoke.

This isn’t a theoretical risk. It’s real, it’s happening now, and it is almost invisible.

The Human Factor: Our Mental Model Is Broken

For thirty years, the internet has trained us in a simple ritual:

If you’re hacked, change your password.

That’s the whole playbook. Everything: security advice, help pages, bank call‑centre scripts, assumes the password is the master key. Lose control of it, and you swap it out. The old key stops working. You’re safe again.

Passkeys violate that model completely.

Users treat passkeys like a convenience feature not as independent credentials that sit deep in the account’s security infrastructure, separate from the password entirely. It has been found in user testing that most people didn’t even realise that adding a passkey was equivalent to handing out a physical house key. And crucially, changing the lock did not take those keys away.

The result? A huge mismatch between what people believe they are securing, and what they are actually securing.

The UX Problem: Passkeys Are Buried Where No One Looks

And this experience isn’t unusual. Multiple independent studies have shown that current passkey implementations consistently hide critical security controls. Research highlight the same problems:

-

Passkeys are named inconsistently (“Security Keys”, “Windows Hello”, “Phone Sign‑in”, “Biometric login”…), making them hard to find.

-

Most platforms do not prominently display newly created passkeys.

-

Many don’t send alerts when one is added.

-

Almost none make passkey auditing part of password‑reset flows.

This is a UX failure of the highest order. Users simply don’t know these things exist, let alone that a hacker can hide one on their account.

Account recovery screens routinely invalidate sessions and tokens—but leave passkeys untouched, because designers fear that revoking them automatically will inconvenience legitimate users.

That design choice creates exactly the vulnerability my friend ran into: an attacker with a valid, invisible, password‑independent credential.

The Implementation Problem: Platforms Are Not Doing Enough

The underlying cryptography of passkeys is excellent. The surrounding ecosystem is not.

This case uncovers multiple systemic weaknesses:

-

Silent persistence — resetting the password almost never revokes passkeys.

-

No unified terminology — leading to user confusion and missed hidden credentials.

-

Buried menus — critical security settings are hidden in non‑obvious places.

-

Weak or missing alerts — passkey registration often goes unreported.

-

Inconsistent revocation logic — each platform handles deletion differently, with some providing no oversight at all.

As a result, even highly technical users frequently miss malicious passkeys lingering on their accounts.

And attackers know this.

In fact, modern infostealers and browser‑injection malware increasingly rely on this exact persistence vector. They don’t need your password. They don’t need to exfiltrate your key. They just need one authenticated session to register their own.

After that, your password resets mean nothing.

The Real Threat: Passkeys Are Too Good

Ironically, the strength of passkeys is exactly what makes them dangerous in a compromised environment.

A passkey sign‑in is:

-

Strong enough to bypass many platforms’ MFA prompts.

-

Treated as a trustworthy login—no unusual‑activity warnings.

-

Often able to validate identity during account‑recovery flows.

To the system, a passkey is the gold standard of identity proof. It trusts it.

So if an attacker has one, all the alarms that normally fire for suspicious logins stay silent.

This is why we need to treat passkeys not as a simple evolution of passwords, but as an entirely different class of identity object: one with the power to silently bypass almost every recovery mechanism a user thinks will save them.

Where We Go From Here

Passkeys can be the future of authentication. But if platforms continue implementing them without proper lifecycle management, visibility, and revocation controls, they will remain a gift to attackers.

We need:

-

A forced audit after password resets. Changing your password should always show you a list of passkeys and ask which to revoke.

-

Mandatory alerts for new passkeys. A silent credential is indistinguishable from a malicious one.

-

Clear, standardised terminology across services. Users can’t manage what they can’t find.

-

First‑class visibility. Passkeys should be on the front page of every security settings dashboard — not buried six clicks deep. Users should be able to see which methods have been recently used for logging in.

-

Education. People need to understand what a passkey really is: a cryptographic key, equivalent to your username and password combined, not a shortcut or convencience.

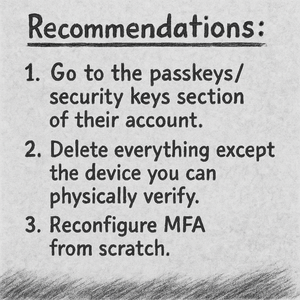

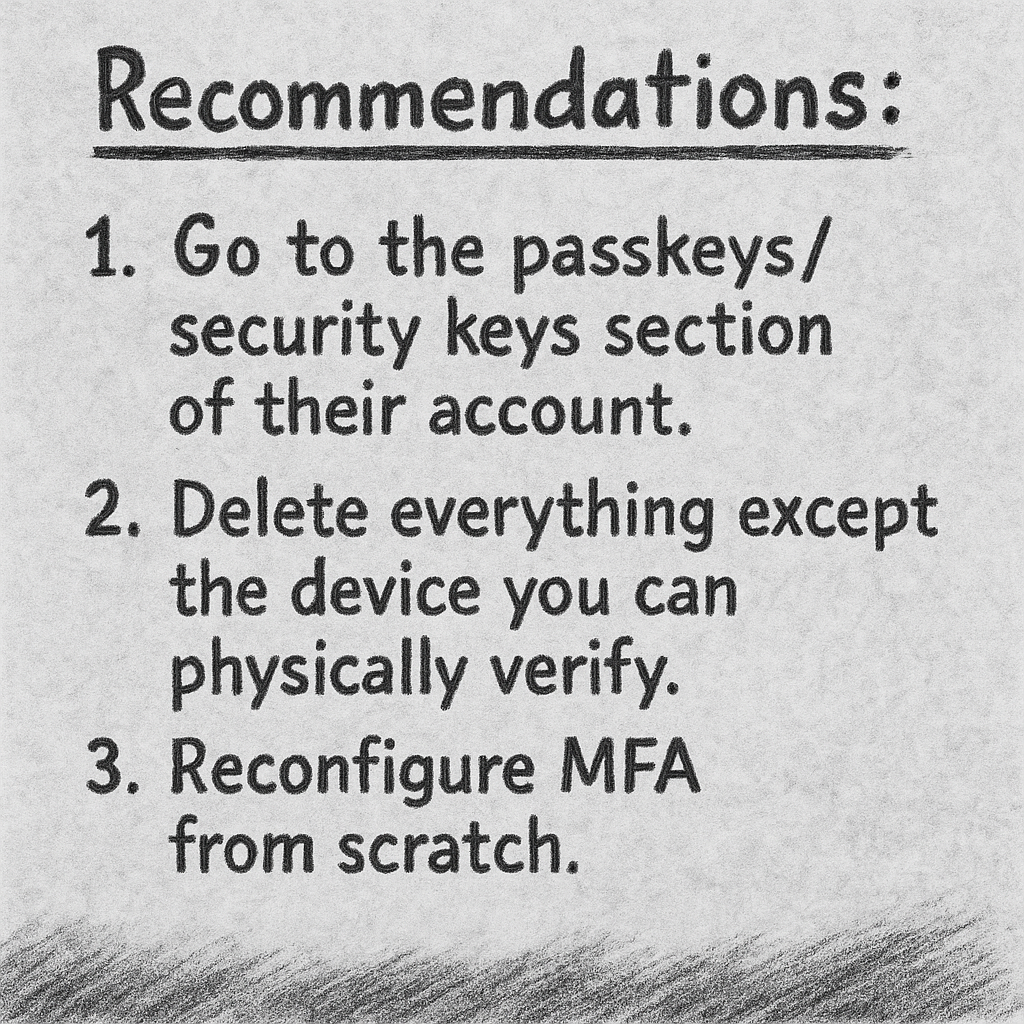

Until Then, Here’s the Only Safe Rule:

When helping someone recover from a hack, changing the password is not enough anymore.

You must:

- Go to the passkeys/security keys section of their account.

- Delete everything except the device you can physically verify.

- Reconfigure MFA from scratch.

Otherwise, you may never get the attacker out.

And that, right now, is the most dangerous thing about passkeys: not their cryptography, but the assumption that they’re harmless.

They are anything but.