The Identity Crisis We Don't Talk About

When I first moved to England, I fell into a bureaucratic rabbit hole. The scattered nature of government systems meant I was somehow issued two NHS numbers and two National Insurance numbers. It was an administrative headache that revealed a surprising truth: for a country so often concerned with who is here, the state frequently struggles to know who is who. (This isn’t just a UK problem; a similar mix-up in Italy, born from a clerk’s confusion over which country Oslo is in, left me with two separate tax codes.)

This personal story is a small symptom of a much larger national issue: a fragmented, inefficient, and error-prone system of identity management across government. Every decade or so, a seemingly logical solution is proposed: a national ID card. And every time, without fail, it ignites a political firestorm before fizzling out.

Why does this seemingly practical idea consistently fail in the UK? The answer lies not in the technology, but in the philosophy behind it.

The UK’s Prescriptive Pitch: Identity as a Tool of Enforcement

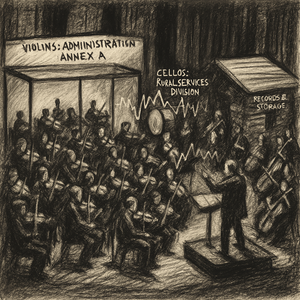

Successive UK governments have consistently framed the concept of a national ID as a tool for the state to enforce its will: a “stick” to beat a particular problem. This approach has a long and troubled history.

ID cards were first introduced as a temporary measure during wartime for crisis management: conscription, rationing, and national security. They were decisively abolished in 1952, not because the war was over, but because their use had crept into general policing, creating a “papers, please” culture that was deemed fundamentally “un-British”. This historical precedent has cast a long shadow. Modern proposals have simply swapped the justifications, focusing on what one commentator called “the moral panic of the day”. In the post-9/11 era under Tony Blair, the rationale was counter-terrorism. Today, the proposed ‘BritCard’ is being sold almost exclusively as a tool to curb illegal immigration by mandating it for ‘Right to Work’ checks.

This enforcement-first framing clashes directly with a core tenet of the British cultural identity: the idea of the “trustworthy Englishman” who is not required to constantly prove their legitimacy to the state. It inverts the relationship, suggesting citizens serve the state rather than the other way around. This approach immediately triggers deep-seated and legitimate fears of state surveillance, “function creep” where a system’s use expands beyond its original purpose, and the creation of a centralised “honeypot” database: a single, high-value target for hackers.

However, the alternative to a central database is not without its own serious, often invisible, data risks. To make the current fragmented systems talk to each other, for instance, to link a record at the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) with one at HMRC, requires a huge amount of data to be pulled and processed simply to establish a confident match. This process of data linking involves accessing far more personal information than is needed for the final analysis, just to be sure that ‘John Smith’ in one database is the same person in another.

This creates its own privacy vulnerabilities, and when it goes wrong, the consequences are severe. Reports have revealed that the data feed from HMRC used to calculate Universal Credit payments is so error-strewn that it may have caused financial hardship for as many as one in four claimants. This is compounded by a poor track record on data security; the DWP has been repeatedly reprimanded by the Information Commissioner’s Office for “basic” data breaches that put vulnerable people’s lives at risk. The public is therefore caught between the visible threat of a single state database and the hidden dangers of a messy, error-prone, and insecure linking process between existing ones.

The European Model: Identity as an Enabling Tool

In stark contrast, many successful European models have framed digital identity not as a stick, but as a “carrot”: a tool that empowers the citizen.

The prime example is Estonia, which introduced its digital ID more than 20 years ago. Crucially, it was not pitched as a security measure but as a way for a newly independent nation to “leapfrog” into the digital age. The entire focus was on utility and convenience. The e-ID gave citizens a single, secure key to access over 3,000 public and private services, from banking and viewing health records to voting online and filing taxes in five minutes. It was sold as a form of freedom and economic progress, not state control.

This philosophy is now being expanded across the continent with the EU Digital Identity Wallet. This is not a state-controlled card, but a user-controlled wallet on your phone. It is built on the principles of user control and selective disclosure. The citizen is placed at the centre of every transaction, deciding exactly what information to share. For example, you can prove you are over 18 to buy alcohol without ever revealing your name or date of birth. It is an architecture of trust, designed from the ground up to serve the user.

The Path Forward for the UK: Win Hearts and Minds Through Utility, Not Fear

The current ‘BritCard’ proposal, with its singular focus on immigration enforcement, is doomed to repeat the mistakes of the past. It is a prescriptive solution that immediately galvanises the opposition and ignores the clear lesson: in the UK, you cannot force a national identity system on the public; you have to make them want it.

The alternative is to stop selling the stick and start offering the carrot. The UK already has the building blocks of an enabling system, such as the GOV.UK One Login service. The strategy should be to:

Focus on Citizen Benefits: Frame the project around solving the everyday bureaucratic headaches people actually face. Imagine a single, secure login to manage your driving licence, update your council tax, book NHS appointments, and check your state pension, all controlled from your phone.

Embrace an Enabling Architecture: Build on the user-centric models seen in Europe. The system must guarantee principles like selective disclosure and data minimisation in law, giving users tangible control over their own data to build trust.

Build Trust Incrementally: As technology specialist Rachel Coldicott noted in a recent BBC podcast, the most effective approach is to allow a system to evolve voluntarily. Let people adopt it because it is useful, not because it is mandatory. A system that proves its value by making life genuinely easier will win support organically.

A Number We Need, An Approach We Don’t

The administrative chaos that leads to people having multiple NHS and NI numbers is real, costly, and needs fixing. A unique, unified identifier is the logical and necessary solution.

The UK’s problem, therefore, isn’t the concept of a national ID number. It is the political obsession with a prescriptive, enforcement-led approach that is fundamentally at odds with the nation’s psyche. By learning from the enabling, citizen-first models in Europe, the government could build a system that people actually want to use: one that makes life simpler and more secure, without sacrificing the principles of a free and open society.