On the surface, the recent wave of US tech investment in the UK, headlined by a £31 billion “Tech Prosperity Deal,” looks like a resounding vote of confidence. Announcements from giants like Microsoft, Nvidia, and Google promise to build the very foundations of our future economy—gleaming data centres and powerful AI supercomputers—right here on British soil. It’s a narrative of growth, jobs, and a UK firmly positioned at the cutting edge of the AI revolution.

But what if we’re looking at this picture upside down? What if, instead of heralding a new era of British prosperity, this deluge of foreign capital is simply accelerating a long-term transfer of value, intellectual property, and wealth from the UK to the US? This investment is a double-edged sword. Without a robust and immediate national strategy to cultivate homegrown success, we risk becoming a high-tech incubator—a nation that brilliantly invents the future, only to sell it off before it matures.

The Architecture of Extraction

The problem isn’t the investment itself, but its structure. The UK provides the fertile ground: world-class universities, a deep well of talent, and a government eager to attract capital. US firms, in turn, provide the funding to build the digital factories of the 21st century. But who owns the factory, the machines inside, and the incredibly valuable products they create?

The answer is clear: they do.

Consider Google’s acquisition of the London-based AI lab DeepMind. Its UK team created AlphaFold, a revolutionary AI projected to add over £400 billion to the UK economy, but its intellectual property and the vast financial returns belong to Alphabet, DeepMind’s US parent. The UK gets the accolades and some high-skilled jobs; the US retains the long-term wealth. And the story doesn’t end there. DeepMind’s success has spun off a vibrant ecosystem of new ventures, with its alumni founding a wave of innovative startups. Many of these begin life in Britain, but without sufficient homegrown capital, they inevitably turn to foreign investors to scale. This perpetuates a cycle where the UK’s breakthroughs ultimately enrich overseas owners.

This pattern is set to repeat on a massive scale. Profits generated from the new infrastructure will flow back to US parent companies, a process aided by corporate structures that have seen major tech firms pay significantly less UK tax than their UK-generated profits might suggest. One analysis estimated that seven of the largest US tech firms may have avoided around £2 billion in UK tax in a single year. This isn’t a partnership of equals; it’s a transaction where the long-term upside is flowing in one direction.

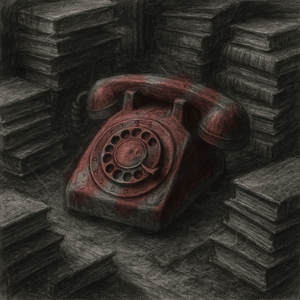

The Great British Sell-Off

This dynamic is supercharged by a chronic weakness in the UK’s own financial ecosystem: the “scale-up gap”. The UK is one of the best places in the world to have an idea and start a company. But when that company needs serious capital to grow into a global leader, it is forced to look abroad. A staggering 60% of late-stage funding for UK startups comes from foreign investors, the majority from the US.

The consequences are predictable and brutal. Our most promising companies are acquired before they can become national champions. In a single 24-hour period in June 2025, two of our leading deep-tech firms: chip designer Alphawave and quantum computing pioneer Oxford Ionics were sold to US rivals. This followed the saga of ARM, arguably the UK’s most important technology company, whose chip designs are in virtually every smartphone on the planet, but whose multi-billion-dollar IPO took place not in London, but on the US Nasdaq.

This isn’t a series of unfortunate events. It is the logical outcome of a venture capital model that prioritises a rapid, high-multiple exit above all else. When the deepest pockets for that exit belong to US investors and corporations, the result is a conveyor belt that systematically transfers the UK’s best innovations and the wealth they create across the Atlantic.

Turning the Model Right Side Up

This trajectory is not inevitable. The recent US investment can be a catalyst for genuine, long-term prosperity, but only if it is met with a bold and deliberate strategy to cultivate, not just incubate, our domestic talent.

First, we must address the scale-up gap. Initiatives like the Mansion House Accord, which encourages UK pension funds to invest in private markets, are a start, but they must be supercharged. We need to think bigger, with policy levers like a UK Sovereign Wealth Fund for Technology and an expanded British Business Bank, both empowered to provide the patient, large-scale capital that allows UK firms to grow to maturity on their own terms.

Second, and more fundamentally, we must champion business models that are not hard-wired for a sell-out. The venture capital model is just one way to build a company, and its “growth-at-all-costs” ethos often creates a toxic “tech bro” culture that prioritises a quick flip over sustainable success.

The UK has a rich history of pioneering alternatives that anchor value and wealth locally. The John Lewis Partnership, owned in trust for its employees for nearly a century, is a testament to a different way of doing business. More recently, companies like Richer Sounds, Aardman Animations, and Riverford Organic Farmers have transitioned to employee ownership, safeguarding their independence and ensuring that the rewards of their success are shared among the people who create it. These models, alongside non-dilutive funding options like revenue-based financing, offer a path for founders who want to build lasting, resilient companies rather than simply fattening them up for a sale.

The current wave of investment is a moment of profound opportunity, but also of profound risk. If we simply act as a welcoming port for foreign capital without strengthening our own fleet, we will become a satellite in a US-led tech ecosystem, not a sovereign power. The UK has the ideas and the talent. The question now is whether we have the political will to build an economy that allows us to own our own upside.